I recently read an article entitled “The humble hero” from The Economist. The article was about containerization of shipments and the impact of container freight innovation on the supply chain worldwide. Some of the statistics were no less than astounding.

Containerized freight was an innovation introduced by Malcom McLean, “an American trucking magnate,” as The Economist magazine describes him. Containerized freight and the first prototype container ship was introduced in 1956. When the costs of shipping containerized versus standard cargo were calculated on the first shipment, the results were amazing. Containerized freight came in at $0.16 per tonne to load, only 2.7 percent of the cost of lading loose cargo on a standard ship (running $5.83 per tonne).

What Was Malcom McLean’s Real Insight?

Malcom McLean was truly a supply chain innovation pioneer—before the term “supply chain” had even been invented.

McLean’s insight was to recognize the real business in which shipping companies were participating.

For hundreds—perhaps thousands—of years, the ships that plied the seas as trading vessels along with the men that owned them and sailed them thought they were in the business of moving freight over the oceans and seas. As a result, all their focus was on improving how the ships moved over the water. They sought to make the ships sleeker, faster and safer for the cargo while on the water. For the most part, they entirely ignored the fact that, while it might take them only three or four days to sail from point A on the globe to point B, it could take the ship two weeks to be unloaded in port B and reloaded for its next journey.

Only 20 percent of the ships time was being spent on the water. The other 80 percent of its time was spent in port being unloaded and loaded. Perhaps it was McLean who first had the innovative insight to recognize that shipping and trucking lines were in the business of satisfying customers with the delivery of goods—satisfying manufacturers and distributors who were trying to get their goods into customers’ hands and satisfying consumers who were trying to get goods from distributors and the manufacturers who made the goods.

McLean recognized that manufacturers and distributors weren’t in one business while his trucking company was in another entirely different business. Instead, McLean perhaps saw that from raw materials producers to retailers, increasing the flow of goods through the pipeline—the “supply chain”—made the world a better place and helped everyone make and save more money.

The Impact of the Supply Chain Innovations

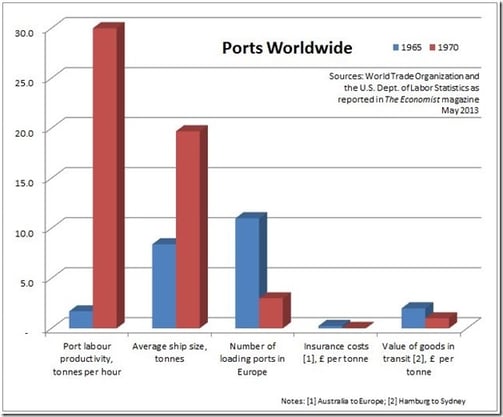

The graph above shows some of the impact of McLean’s innovation and improvements in the flow across the supply chain. Allow me to summarize some of the impacts on the supply chain over the five year period between 1965 (when containerization was adopted worldwide) and 1970:

- Labor productivity at the docks grew by more than 1,760 percent. This, in turn, allowed shipping companies to increase the size of their ships (from an average of 8.4 tonnes in 1965 to 19.7 tonnes in 1970) while, at the same time, spend less time in port.

- Door-to-door delivery times dropped dramatically to half or less and became more consistent at the same time.

- Reduced risk was a huge side-benefit of containerization: falling demand for labor on the docks reduced the bargaining power of the unions and slashed the number of strikes and slowdowns that hampered the movement of freight through the ports. Additionally, since containers could be sealed at the factories, losses from theft and other causes declined greatly. This reduced supply chain risk was manifested in sharply falling insurance costs. By 1970, insurance rates on shipments fell to about one-sixth of their 1965 rates,

- Ports became bigger and more efficient, while smaller, less efficient ports were closed. Europe had eleven major loading ports in 1965. By 1970, it had only three. This led to greater stability and reliability in both the time and costs related to transshipment of goods.

- Increasing speed and reliability of shipments across vast distances enabled increasing reliance upon just-in-time production and inventories, further increasing efficiencies and reducing costs.

- More types of goods could be traded economically in closed containers. Goods that may previously been subject to huge in-transit losses from theft or damage could now be traded routinely worldwide.

The broader array of goods helped accelerate the industrialization of emerging economies in China and much of the Pacific rim.This can be seen in the sharp fall of value of goods in transit between 1965 and 1970.

Extrapolating from this Lesson

Too many times, in businesses I visit, their view is too much within their own organization and industry. Like the shipping companies of a now bygone era, they think what they do every day is what their business is all about. Generally, it is not so. Allow me to give you a couple of examples that come to mind:

- In the 1980s, IBM and Microsoft saw themselves as being companies that supply computers and operating systems to businesses. Reluctantly, IBM was persuaded that they should also supply computers to “people”—hence, they finally introduced “the personal computer” or “PC.” On the other hand, Apple Computers saw themselves—especially with the introduction of the Macintosh computer—as a company that provided a way to get the machine out of the way and let the people improve their lives by leveraging computing for fun and profit. It was Apple Computers and the Macintosh that forced Microsoft and the “PC” computing industry to give us the Windows operating system. I cannot imagine the vast scale of computer adoption worldwide if we all still had to use the arcane “MS-DOS” commands and non-WYSIWYG applications to trudge through our work.

- As an early adopter of cellular phone technology (I’ve been carrying a cell phone since about 1987), I can testify that leader Motorola appeared to have been a company that saw itself as delivering nothing more than technology to business. For Motorola—until driven by innovation by their competition—cell phones were cell phones, and nothing more. It took innovative companies like Nokia and, ultimately, Apple, too, to cause this industry to see that they could deliver “better living” to millions in hundreds or even thousands of ways.

Don’t get your head so buried in your own business or industry that you find yourself thinking that your business is “making X” or “delivering Y” or “selling Z” to this or that market. If you do, you will miss opportunities for innovation and higher profits. If you’re not in the business of making people’s lives better through an innovative and connected supply chain, chances are you are not making as much money today as you could be. Here’s the question I ask almost every client when I meet with them the first time:

What are the five or ten things that are keeping your firm from making more money tomorrow than you are making today?

Chances are, the answers are not what you think they are.

We would like to hear from you on this matter. Please feel free to leave your comments here, or contact us directly, if you prefer.

Read more about how containerization changed the world in these great books:

Box Boats: How Container Ships Changed the World: Brian J. Cudahy: 9780823225682: Books

Box Boats: How Container Ships Changed the World: Brian J. Cudahy: 9780823225682: Books The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger: Marc Levinson: 9780691136400: Books

The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger: Marc Levinson: 9780691136400: Books